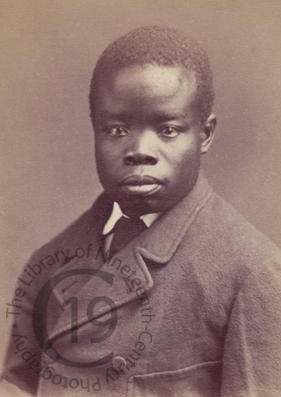

Jacob Wainwright

Jacob Wainwright had a full life, but in recent years in the UK his memory was reduced to a negative portrayal in a memoir, and interpretation of fragments from his “lost” diary. His own words, and the positive things said of him at the time, have been forgotten. Belong volunteers have thus revisited his full diary, which survived in German and French, and other records, including a recently uncovered Nottingham speech found in Derbyshire archives, so that his voice can be heard again.

Who was Jacob Wainwright?

Born somewhere between 1849 – 1859, Wainwright was a member of the Yao people on the south of lake Malawi in East Africa, with a given name of Yamuza. At the age of 7 he was taken as a slave by Arab slave traders but rescued by a British Warship and christened under his new name, Jacob Wainwright after being baptised and accepting Christianity as his new religion. He spent time in British India, finding refuge and education at the Church Missionary School Asylum in Bombay where he would begin his studies as a missionary. He would go on to join the Royal Geographical Society’s Livingstone Search and Relief Expedition in early 1872, aged around 14, which would prove to be an unsuccessful attempt to find a missing David Livingstone, the famous Scottish explorer and missionary, and it wasn’t until the Stanley Expedition that Livingstone was found, with Wainwright once again accompanying the search team. After finding the celebrated explorer, Wainwright would continue to travel with him for one final adventure, until Dr. Livingstone died (modern Zambia), on 1 May 1873. Wainwright and two other Africans bought his body the 1,000 miles to Zanzibar to prepare for its journey back to the UK.

As the most literate member, Wainwright would write a letter to the relief expedition which included Livingstone’s son, informing them that Dr Livingstone had died. At Zanzibar, it seems that the British assumed that Wainwright was the leader, despite his youth, because he was the only African servant who could speak and write in English. He was sent with the body for England, where Wainwright would guard Livingstone’s coffin on its journey to Britain. Wainwright was the only African among the eight pallbearers at the explorer’s funeral in Westminster Abbey on 18 April 1874.

Jacob Wainwright in Nottingham

Jacob Wainwright visited Nottingham in 1874 to give a lecture on slavery at the Mechanic’s Institute on June 17, a place where Charles Dickens had lectured several times in the 1850s. Born as Yamuza between 1849-59 into the Yao people in what is now Malawi/Mozambique, in his lecture Wainwright talked about his experience of being enslaved as a boy, then rescued and taken to Mumbai to be educated at the Nassik school, later travelling with David Livingstone in Africa, and documenting the expedition to bring Livingstone’s body to Zanzibar. He went on to detail what he wished to continue when returning to Africa: bringing aid to newly liberated slaves and continuing Livingtone’s work as a missionary, spreading the word of God wherever he could. Jacob Wainwright visited Newstead Abbey, near Nottingham, the ancestral home of the Byron family. At that time, it was owned by William Frederick Webb, an explorer, who had known Livingstone and wanted to meet Wainwright.

The UK tour

Before coming to the city, he had lunch with Queen Victoria and was a pallbearer at David

Livingstone’s second funeral, in Westminster Abbey. He also met many anti-slavery campaigners, and various eminent people, including the Bishop of Norwich, lords and ladies, and prominent bankers. Press coverage was favourable in Britain, and he was also interviewed by Henry Morton Stanley for the New York Herald.

His original diary, described by Queen Victoria as ‘most curious’ in her own diary 1 of April 30 1874, sadly disappeared, although a translation into German survived.

A Newstead ‘”no”

In Newstead his visit seems to have caused some consternation, if we believe the memoir by Alice Fraser (Alice Spinner), the Webb’s daughter. She describes his visit, which followed that of two other African Livingstone companions, Susi and Chumah, as “far less agreeable” “He was, perhaps, then four-and-twenty, and, no doubt, in his way, and under proper control, a useful servant” She describes him as “…remarkably ugly… , and cites biblical proverbs about “a servant when he reigneth”, claiming he had “grown so far above himself”.

The family seemed surprised that the missionary expected Wainwright to join them for lunch, with Fraser claiming Dr Livingstone insisted on keeping African servants under “kindly but due discipline”. However, Wainwright had recently lunched with eminent people, the Queen included. Why would he and his mentor not eat with the family? Fraser says “…it was not a mere question of colour, but of the individual”. Race and class prejudice seem to have come into play.

This memoir, and the claim he had “internalised colonialism” based on his diary fragments which appear to show criticism of other Africans, mean much of his story has been lost in translation.

Jacob Wainwright the geographer

His diary, translated back into English from German and French translations, shows a rounder picture, of someone who described what he saw and often praised the lands and people they visited. He also describes a land in conflict from slave raiding and emerging colonisation.

In his speech in Nottingham, he says “We had long journey to coast – about 10 months – and sometimes we had to fight natives – and we met with very great difficulties…”. And in the diary he notes that “wilderness areas are haunted by robbers”, and describes the Wakhonongo as a “courageous, industrious and strong race of men, and their music is the sweetest among all of Africa’s nations…”. He describes the land of the Unyamwezi as “Well cultivated”, the town of Mtondo with its people who “busily till their fields year after year”, while another people are said to take refuge on islands on a lake from raiders. It is all a long way from the surviving English descriptions of “wicked natives”, which distorts Wainwright’s meaning.

Playing Detective

Meanwhile, Alice Fraser claims the Livingstone’s needed the money which the explorer’s diary would bring in (“The financial affairs of the whole Livingstone family were, at this juncture, admittedly at a low ebb…”). Conveniently, Wainwright’s diary went missing before it was published, despite being described as “in press”.

Or did it? What if Queen Victoria simply never handed it back, and it is now gathering dust in a royal archive? Or kept in a University library?

Jacob Wainwright died in 1882 in Urambo, now in Tanzania. A memorial still stands to him there.